The 1918 Spanish flu pandemic was the

deadliest of all modern pandemics, killing 17-50 million people from February 1918 to April 1920.

One of the interesting factors of the Spanish flu, as it is known today, is that viruses were too small to see

with the microscopes of the day, so people were

not even aware that viruses existed.

What they were able to find in patients back then, to link the entire pandemic together,

was bacillus influenzae

– the bacteria of influenza, which was believed to be the cause

of influenza until the 1930’s. Some recent research found that most of the 'Spanish flu'

deaths were, as diagnosed at the time, due to these

bacterial superinfections,

which

themselves can be exacerbated by any illness weakening the body.

So, it is possible that deaths attributed over two entire years to the 'Spanish flu' could

have been from a wide range of illnesses that

result in pneumonia, including coronavirus colds, etc.

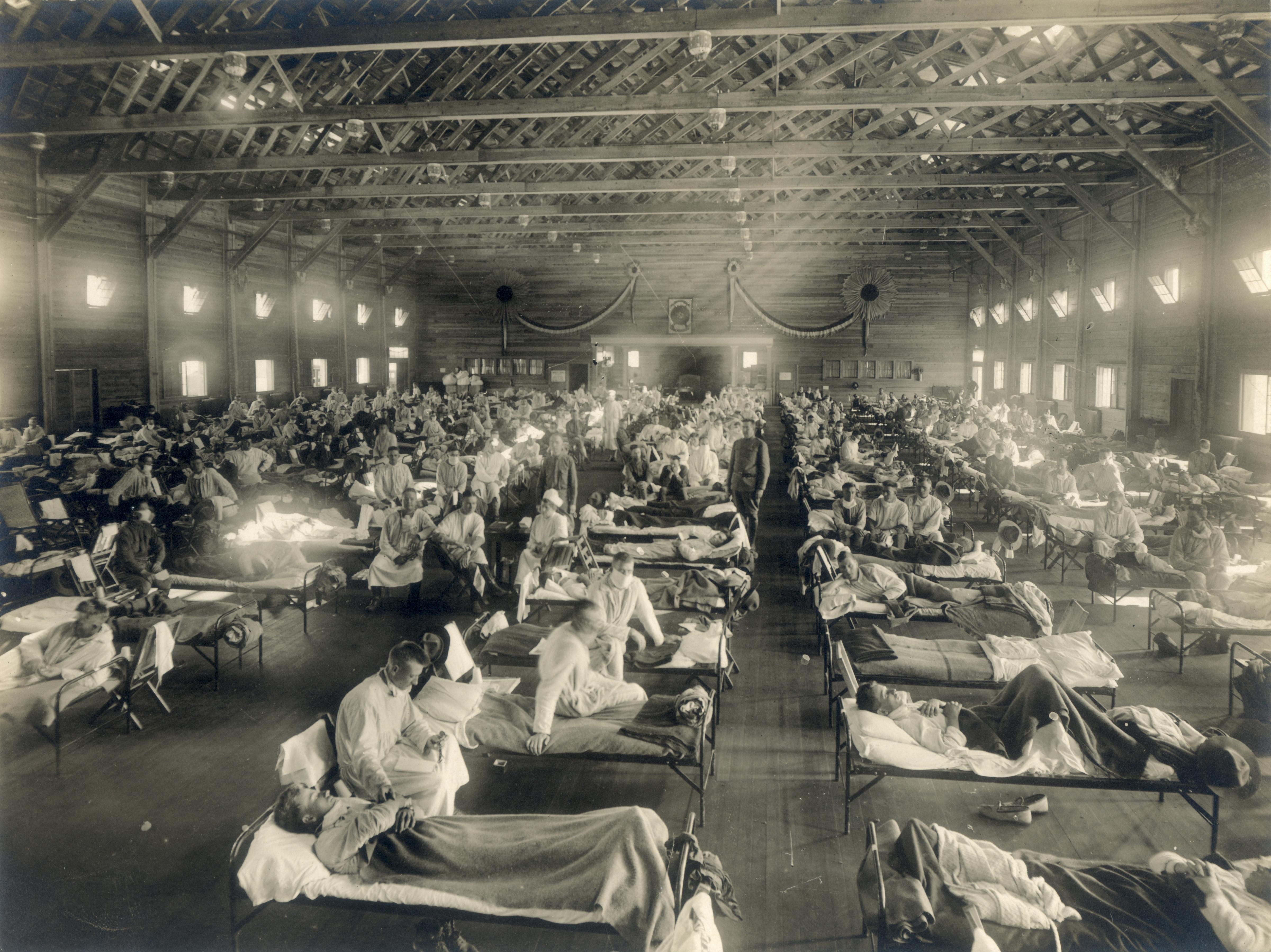

Bacterial infections require close-quarters with other

infected individuals - almost like in the famous photos of open-air warehouses

filled with beds, in which patients would cough up

into the air, and all-over other patients.

As patients died of the bacterial infection they got at the hospital,

those newly empty beds would be filled with new patients suffering from cold or flu,

who would've otherwise recovered in a week or so at home,

only to be infected with bacteria from the patients next to them that would make them sicker,

and eventually kill them, thus opening up that bed for the next patient.

The first wave

of the 1918 pandemic,

in March-June 1918, traditionally cold season,

caused only a mild elevation in what was reported as “flu-related deaths".

The second wave in

September-December, traditionally flu season, saw deaths at a level that could easily

be described

as a different disease, and strangely, seemed to affect young people more than the

usually vulnerable old.

The third wave was from January-June 1919, again, traditionally cold season,

and behaved differently than the second wave -

closer in deadliness to the first wave, only slightly more so. A fourth wave,

again, more minor, and in cold season,

was seen in some places in January-March 1920.

A few preserved samples from the most-deadly, and therefore, most studied, second wave,

were later positively identified as having an influenza virus infection.

However, given that bacteria was the presumed cause throughout this time,

and the reason we think of these two entire years as one pandemic 'event'

is because of the way it was recorded and taught, one possible view of

these different waves, is that each was driven by a different disease -

a cold, the identified flu, a cold, and then a cold, in turn.

We then assumed that they were all the same disease, both because it was similarly

'bad' throughout this period, and because that was the prevailing view after most

of those dying were found to have the same bacteria, by the microscopes they had available at that time.

But what if other factors

led to a series of bad airborne diseases over those two years?

It is possible that the first 1918 season's 'bad cold' set off a wave of

virus-avoidance behavior in communities, which was then fully

in force by the second wave.

If people were frightened into believing that there was a 'super-illness'

going around, particularly

in younger individuals who

hadn't seen bad cold seasons before, they would feel that the thing to do

was to crowd into hospitals for treatment, where they would

then be exposed to the bacterial infection that would kill them.

Interestingly, China was hit by this second wave flu, but for them,

it was a mild season,

and they did not experience the level of deaths

seen elsewhere around the world, suggesting that even that second wave flu was just an ordinary flu,

with nothing special about it except

the virus-avoidance behavior of much of the world in dealing with it.

The virus-avoidance culture, and associated hysteria driving people to the hospital,

then began to dissipate after the third ‘bad cold’ wave, leading to less impactful

airborne illnesses.

As always, there would be many contributing factors to overall health results - another possible contributor

to the deadliness in 1918 was the level of pollution in a newly industrialized

world. This was decades prior to emissions controls, and it was difficult to see across the street in many cities

across the United States. So, there was likely a much larger vulnerable population to respiratory disease worldwide

back then, similar to what we see in Covid-19 deaths in countries like Thailand,

with high levels of pollution.

It is difficult to know for sure what had happened in the past,

particularly when all the types of evidence we might consider today,

were not available back then. But one thing is for sure: when human

observation is the lens through which an event is seen, it is always

helpful to question whether the prevailing view is built upon a

chain of misconceptions.

While there are many reasons why humans are often incapable of admitting

mistakes,

one of the biggest indicators that the

response to the Spanish flu was considered to be a failure by those who

lived through it, was in survivors of the Spanish flu

who led the response to pandemics

several times more deadly than Covid-19

in the 1950's and 1960's, who rejected

Virus-Avoidance Strategies.